Let’s talk about the notorious pirate Blackbeard’s head, the one fixed atop his shoulders before it was unceremoniously removed by a sword at Ocracoke on Nov 22, 1718.

Blackbeard’s detached head is one of the handful of reasons why he became America’s most famous pirate soon after his death. He was not known then for how successful or how wealthy he was or where his treasure was buried; not for how many houses he had; and not for how many wives and girlfriends he had. That notoriety, and those myths, came later.

He became a household name in the 18th century for how he had been gruesomely decapitated in his final fight and how his head was reported to have been impaled upon a pike staff and displayed to visitors at Hampton, Virginia.

Take away his unique nickname, his out-of-fashion beard, and his spectacular downfall at Ocracoke Island, and Blackbeard would have just been your run-of-the-mill, garden-variety pirate. And there wouldn’t have been movies & television documentaries made about him.

You know the story: After the battle on Nov 22, 1718, Royal Navy Lieutenant Robert Maynard purportedly snatched Blackbeard’s head by its hair and strung it up so that it would hang from the bowsprit of his sloop as a sort of literal figurehead—or “hood ornament” for you non-boaters—for shock value when he sailed into the pirate’s home port of Bath.

No doubt it worked. You see, even though the notorious arch-pirate was dead, his severed head with its blood-caked beard and hair, taut leathery skin, and contemptuous frozen grin, was not done striking terror in the hearts of its beholders. The sight may no longer have caused dread for his victims but it did strike horror and grief for those who were once his friends, admirers, and townsfolk.

From Bath—if we are to believe the fertile imaginations of the many pirate scholars and archaeologists who have parroted this odoriferous folktale over the centuries—the head continued to dangle from its precarious perch all the way back to the Chesapeake Bay. Now, imagine that.

It’s well-documented that it took six weeks for Maynard to return to Virginia—a journey of 300 nautical miles. Consider, for the moment, the likelihood that Blackbeard’s head would have survived the journey, swarmed by flies and maggots while crossing Pamlico Sound, pecked and greedily clawed by voracious seagulls, and repeatedly dunked beneath the winter waves in the Graveyard of the Atlantic as Maynard’s little flotilla beat its way against northeast gales. What if, when the sun rose after a stormy night at sea, the head, or whatever was left of it, was no longer hanging from the bowsprit? Oops! There goes our bounty!

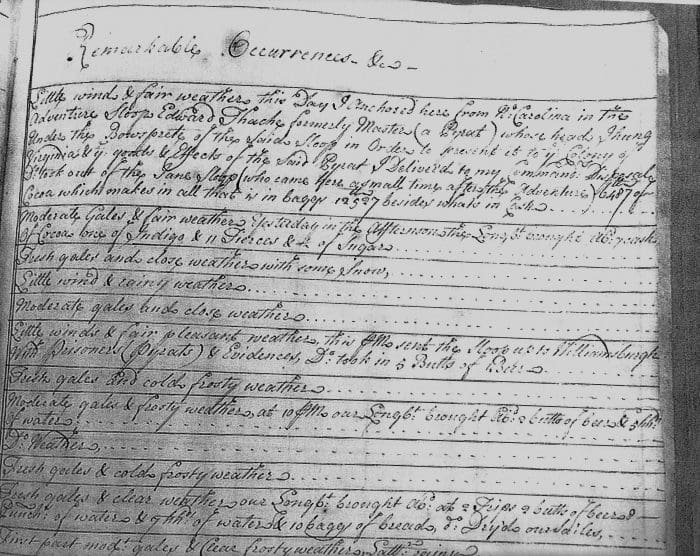

The most reliable source in historical research is the handwritten testimony of an eyewitness who had direct knowledge of an event. Thus, we turn to the very words of Lt. Maynard, recorded in his own journal on January 3, 1719, six weeks after the battle:

“Little winds and fair weather. This day I anchored here from No. Carolina in the Adventure sloop Edward Thache formerly master (a Pyrat) whose head I hung under the bowsprit of the said sloop in order to present it to the Colony of Virginia…”

So, there it is. Blackbeard’s rotting head did not see the light of day until January 3rd, when it was almost certainly removed from a cask filled with lime. For the British sailors tasked with attaching the six-week-old relic to the bowsprit, it must have been an odious honor.

But from then and there, what happened to the head? There are numerous myths and legends concocted by various writers over the past 300 years that mostly follow a similar storyline—Blackbeard’s skull, or a portion of it, was turned into a silver-plated punch bowl that was used by a secret fraternal society to honor the world’s most notorious pirate.

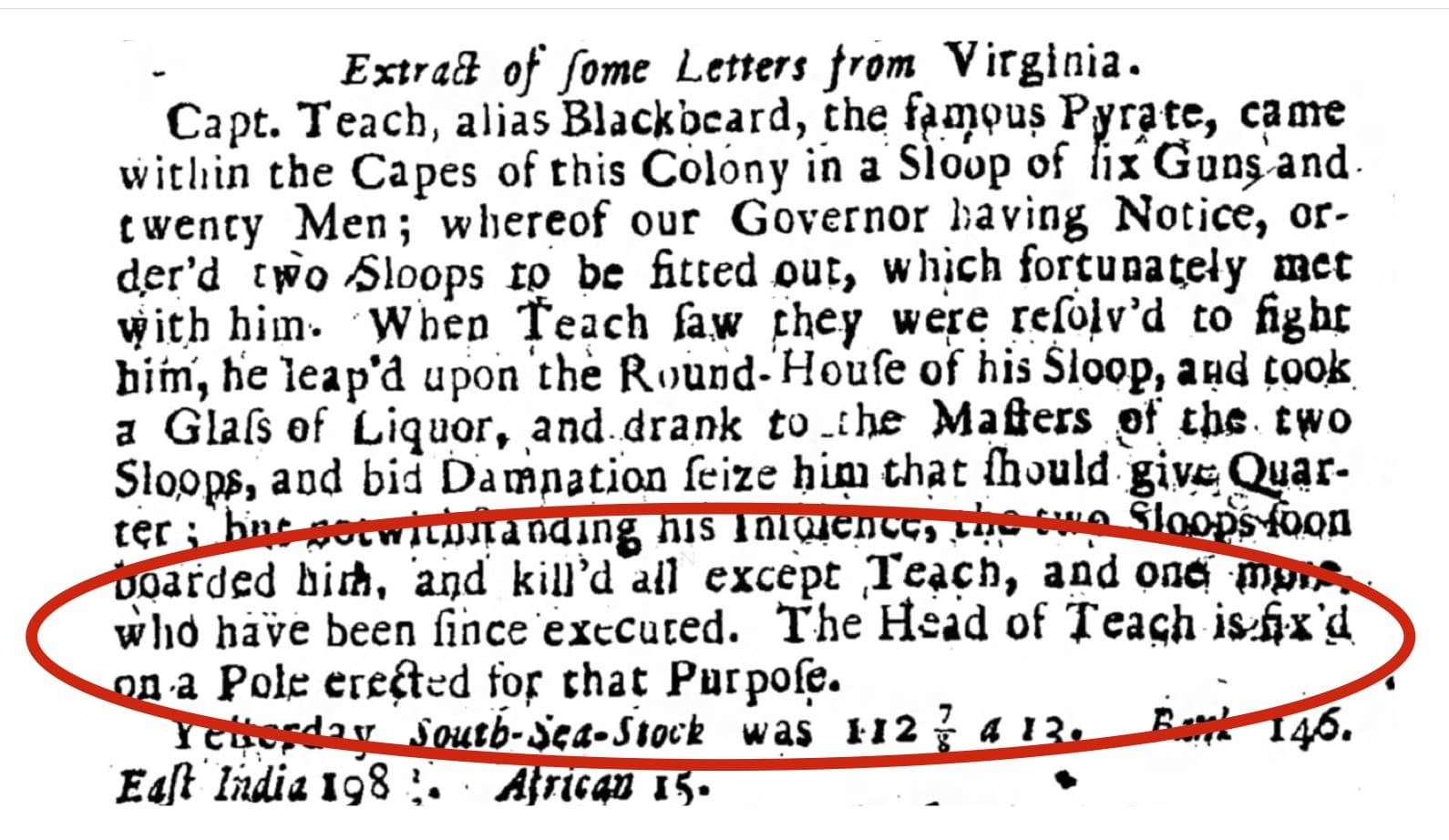

It all started with the London newspaper, The Post Boy, published on April 9, 1719. The newspaper reported a preposterously inaccurate account that “the famous Teach, alias Blackbeard” was captured alive, not at Ocracoke but in a battle in Chesapeake Bay, nearly three months after he had actually been killed. The dubious newspaper account was the first and only period source claiming “that the head of Teach is fix’d upon a pole for that purpose.” Even though historians have accepted and repeated the story as fact, there exists no official government or Royal Navy document that describes Blackbeard’s head stuck on a pole.

The legend, however, was just getting started. The antiquarian John Fanning Watson, 124 years after Blackbeard’s death, wrote the book Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, in the olden time. Likely using the 1719 London newspaper account for his inspiration—especially since it was the sole source of the “head on a pike” story—Watson embroidered the tale even more, writing:

“Afterwards, when his head was taken down, his skull was made into the bottom part of a very large punch bowl, which was long used as a drinking vessel at the Raleigh tavern at Williamsburg. It was enlarged with silver, or silver plated; and I have seen those whose forefathers have spoken of their drinking punch from it, with a silver ladle appurtenant to that bowl.”

Punch bowls in places like Williamsburg not long after Blackbeard’s death were generally made of ceramics or decorated china. Assuming that the skull survived the ravages of an untold number of seasons on a pole, silver was a rare commodity in the 1720s and it is difficult to imagine a sufficient amount of it being used to enlarge a punch bowl, the bottom part of which included the notorious pirate’s skull.

The other problem with Watson’s Raleigh Tavern legend is that, according to a 1932 Colonial Williamsburg historical resource report, it’s uncertain if the tavern was even there when Blackbeard’s head would have been around.

But Watson was not the only writer who concocted a story revolving around Blackbeard’s skull being fashioned into a ceremonial drinking cup. The late Greenville district court judge Charles Harry Whedbee loved a good fish tale, especially those about his beloved Outer Banks. The stories he collected over the years were turned into a highly popular series of five little books featuring his favorite legends of coastal lore.

One of Whedbee’s recurring topics was Blackbeard. In his fifth and final book, Blackbeard’s Cup and Other Stories of the Outer Banks, the judge wrote that the pirate had built himself a large house on Ocracoke, “two stories high and containing many large rooms,” which was known over the years among the islanders as “Blackbeard’s Castle.” Somehow the pirate managed to accomplish this during the few weeks he was at the island in 1718.

The structure Whedbee referred to was located at Springer’s Point, near the old well. He described the time in the 1930s when he and a fellow law student at the University of North Carolina visited Ocracoke. While there, they were invited to participate in a secret fraternal ritual with a dozen bearded, blue-eyed, “hoi-toiders” inside Blackbeard’s Castle.

Illuminated only by the wavering light of a kerosene lantern, the secret conclave gathered with great solemnity around a large table and took turns sipping a special communal libation from a peculiarly-shaped silver cup with the words, “Deth to Spotswood,” carved around the rim.

The participants also chanted the cup’s oath, over and over, in their heavily accented, gravely voices: “Deth to Spotswood.” In case you didn’t know, Alexander Spotswood was Virginia’s pompous lieutenant governor who ordered the killing or capture of Blackbeard.

After the first round of toasts, the young law student and future judge was informed that the vessel from which he and his companion drank was none other than the skull of the ritual’s revered honoree, Blackbeard. The judge-turned-folklorist invented the tale that, contrary to the facts in Lt. Maynard’s logbook, Blackbeard’s head was never taken to Virginia but instead his skull was fashioned into a punch bowl by a Bath Town silversmith funded by some of the dead pirate’s grieving friends (even though silver was even scarcer at Bath than it was at Williamsburg). Whedbee surmised that the silver-plated skull eventually found its way to Ocracoke where it was used by the secret Deth to Spotswood society.

Now for some historical facts. In the long history of literature and plot devices, there is truly nothing new under the sun. The English have always had a macabre fascination with human heads and they were especially keen on impaling the heads of traitors on pikestaffs, or lances, and then displaying them to the public as a means of discouraging bad behavior. The south end of London Bridge between 1300 and the late 1600s was festooned with the rotting heads of miscreants.

Typically, the heads in London were dipped in tar in order to prevent decomposition and also to keep birds from devouring the Monarch’s trophies of justice. Oliver Cromwell’s head was stuck upon a pole atop Westminster Hall where it remained, sort of like a weather vane, for more than 20 years. One day, a high wind blew it down and it was taken home by one of the King’s guards. Awhile later it was sold for £100 to a collector and member of Parliament named Horace Wilkinson who purportedly popped it out for fun at parties.

I believe that the Philadelphia antiquarian John Watson’s tale of Blackbeard’s head displayed at the entrance to Hampton harbor may have been partly inspired by the story of Cromwell’s head which was in the news while he was writing his book. As for Whedbee’s story, “Blackbeard’s Cup,” the house he claimed to have visited to participate in the secret Deth to Spotswood ritual, often referred to as “Blackbeard’s Castle,” was, at the time, the summer residence of the Springer family. Although the origins of the structure are undetermined, it was unlikely that it, or any other manmade structure, was there in Blackbeard’s day.

My research on skulls employed as drinking cups, however, led me to an unexpected source and one that very likely gave Watson the idea—Whedbee as well—to spin the yarn of Blackbeard’s silver plated skull.

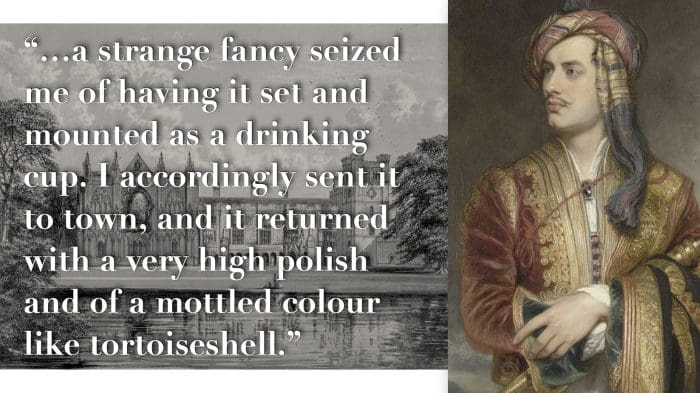

In 1824, about the time that Watson was gathering material for Annals of Philadelphia, the English poet Thomas Medwin published a book titled Journal of the Conversations of Lord Byron. In Medwin’s book, he quotes Byron who described the years when he lived in his ancestral home at Newstead in Nottinghamshire, England:

“There had been found by the gardener, in digging, a skull that had probably belonged to some jolly friar or monk of the Abbey… Observing it to be of giant size, and in a perfect state of preservation, a strange fancy seized me of having it set and mounted as a drinking cup. I accordingly sent it to town, and it returned with a very high polish and of a mottled colour like tortoiseshell. I remember scribbling some lines about it; but that was not all. I afterwards established at the Abbey a new order. The members consisted of 12, and I elected myself grand master. A set of black gowns, mine distinguished from the rest, was ordered, and from time to time, the [cranium] was filled with claret, and, in imitation of the Goths of old, passed about to the gods of the Consistory, whilst many a prime joke was cut at its expense.”

Byron’s recounting of his secret order of a dozen members dressed in black gowns at chapter meetings drinking wine from a polished skull drinking cup sure sounds a lot like Judge Whedbee’s attendance at Ocracoke’s secret Blackbeard society, which also consisted of a dozen members.

In popularizing the legend of Blackbeard’s skull, Lord Byron, Watson, and Whedbee, and innumerable other writers have, intentionally or not, co-opted a tradition originally found in Knights Templar mythology, and rumored to be practiced in modern Freemasonry as recounted in books like Dan Brown’s The Lost Symbol. Skulls have long been associated with the Templars and there are those who believe modern Freemason rituals mimic some of the ancient Templar practices, where initiates of the secret society drink a bitter wine from a human skull cup. The somber ceremony is intended to be symbolic of the bitter cup of death, from which everyone must drink eventually.

There are those who believe the allegory assumes an even darker form—that the celebrants invite the sins of the person who once inhabited the skull to be “heaped upon them,” and to appear against them on Judgement Day should they ever willingly violate their solemn vow and steadfast obligation to their organization and brethren.

I don’t know about you but I’m not sure that I would want to face Judgement Day with Blackbeard’s sins heaped upon me even though my research into the pirate revealed that he was not nearly as ruthless as pop-culture has made him out to be.

What truly happened to Blackbeard’s head? It’s anyone’s guess.

About the author

Kevin Duffus is an award-winning North Carolina historian, filmmaker, and author whose previous works include The Inventor Reginald Fessenden and the Origins of American Radio on North Carolina’s Outer Banks, The Last Days of Black Beard the Pirate, The Lost Light: The Mystery of the Missing Cape Hatteras Fresnel Lens and War Zone—World War II Off the North Carolina Coast.

Known for his exhaustive archival research and his ability to uncover forgotten truths, Duffus has spent decades documenting the hidden histories of the Carolina coast.

His latest work, he says, aims to do for Fessenden what others have done for the Wright brothers — “to finally put his achievements in their proper place in world history.”

“Fessenden is every bit as significant as Wilbur and Orville Wright,” Duffus said. “His experiments on the Outer Banks laid the groundwork for nearly every form of human communication today.”

The post On Nov. 22, Blackbeard lost his head — and launched 300 years of myth appeared first on Island Free Press.

Add to favorites

Add to favoritesCredit: Original content published here.