Frisco is on the verge of regaining one of its iconic landmarks, roughly a century after it disappeared.

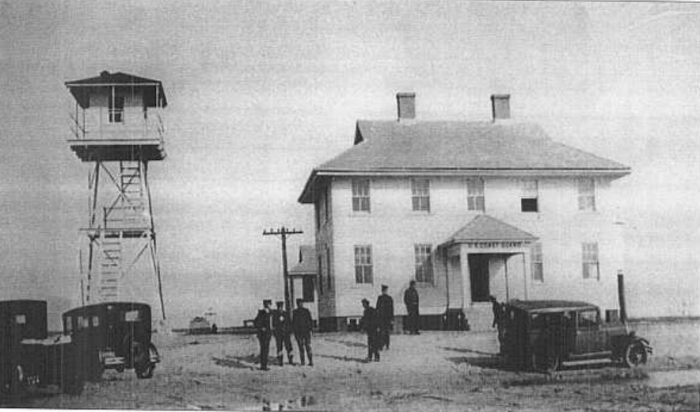

Contractors are working on creating a life-size replica of the lookout tower that once accompanied the 1918 Creeds Hill Station, now a private residence on the southern outskirts of Frisco village.

The project has caused many travelers along N.C. Highway 12 to slow down and turn their heads, as for the past several months, the site has been a hotbed of unusual construction activity.

Pilings were driven 50 feet deep to hold the structure in place. A metal tower has been transported to the site, along with the shiny frame of what looks like a large gazebo.

It’s unlike any development project on Hatteras Island, and Emery Chickey of Eastern Coast Construction, the subcontractor building the tower, says that the work from design to installation has been both unusual and rewarding.

“It’s a very unique project. You don’t come across many lookout towers on the Outer Banks, and we’re building it on a very unforgiving landscape, so it has to be built to last,” said Chickey. “We’ve been fortunate with the weather, though, and it’s going to be done sooner than you think.”

A brief history of Creeds Hill Life-Saving Station

The U.S. Life-Saving Service (USLSS) was the precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard, and was founded in the 1800s as a federal government-funded organization that could respond to the countless shipwrecks that were plaguing the East Coast.

The first seven U.S. Life-Saving Stations in North Carolina were established in 1874 – Chicamacomico, Little Kinnakeet, Bodie Island (later named Oregon Inlet), Nags Head, Kitty Hawk, Caffey’s Inlet, and Currituck’s Jones Hill – and the original Creeds Hill Station was built shortly after in 1878.

“The original location of Creeds Hill was on the beach abreast of Sandy Bay, about two miles east of the current 1918 building in Frisco,” said James Charlet, historian and author of “Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks” Volumes I and II. “It was abandoned due to shoreline erosion, which was quite common for many Outer Banks stations.”

(Sea Chest)

The first 1878 Creeds Hill Station followed a similar design to its island neighbors, and was a one-story station that sat on a patch of raised terrain, known locally as “Creeds Hill.”

After 30 years of service at this original site, a new location and a new design were implemented shortly after the USLSS became the U.S. Coast Guard.

The title of the present-day Creeds Hill site was acquired by the government in 1917, and plans were drawn using a Chatham-Type design, created by USLSS architect Victor Mendleheff.

These styles of stations were generally two-story, five-bay, gable-on-hip buildings with a Tuscan columned portico or an enclosed three-bay entrance porch, although every finished structure had slight variations.

While many of these stations were erected in Chatham, Massachusetts – hence the name – only seven of North Carolina’s lifesaving stations were Chatham-Types, including the Hatteras Island stations of Big Kinnakeet, Hatteras Inlet, and Creeds Hill. Of these three, only Creeds Hill remains.

With plans for the larger and modern station in hand, the station buildings were erected in 1918. Buxton carpenter Rocky Rollinson, alongside Joe Daily, reportedly built the Creeds Hill Station, and later the Bodie Island Station, which has also disappeared from the Outer Banks landscape.

In addition to the two buildings that are visible today – the main station and a mess hall or “messroom” – the station also included two cisterns, a stable, and the long-gone lookout tower.

Only 60 feet from the high tide line, the lookout tower became a valuable asset for station personnel who were on constant alert for shipwrecks along the Outer Banks’ notorious “Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

At its height in 1914, when the USLSS was segmented into 13 districts, North Carolina had 34 stations, and was only exceeded in number by New Jersey, which had 41 stations.

This abundance of stations was intentional, as the heroes of the USLSS performed thousands of recuses annually in less-than-ideal conditions.

In fact, before the USLSS merged with the Revenue Cutter Service in 1915 to become the U.S. Coast Guard, the national organization had responded to 28,121 vessels in distress, and saved 177,286 lives out of 178,741 in peril at sea.

Creeds Hill had a notable role in this history of heroism, too. Keeper Pat H. Etheridge was awarded a gold medal for the ocean rescue of nine members of the barkentine Ephraim Williams on December 22, 1884.

For rescuing the crew of the steamer Brewster on the Inner Diamond Shoals on November 28, 1909, the German government awarded members of the Creeds Hill and nearby Cape Hatteras crews watches and money. (Creeds Hill Surfmen Horatio S. Miller and David E. Fulcher each received $15, while Eugene H. Peel, the station’s Keeper, was presented with a silver watch.) In 1911, the federal government also awarded lifesaving medals for the Brewster rescue: Peel received a gold medal and Surfmen Fulcher, Urias o. Gaskins, and Willie H. Austin each received silver medals.

Following the rescue of the five crewmen of the trawler Anna May, which sank off the Diamond Shoals on December 9, 1931, Chief Boatswain Mates Monroe Gilliken and Erskine Oden were awarded silver lifesaving medals.

In short, Creeds Hill had a long legacy of service from 1878-1947, spanning two stations and the transition of the USLSS to the Coast Guard, until the site was abandoned in 1947.

On the same day that the federal government gave up its ownership in June 1947, V.L and Lois Rollinson, John and Pauline Rollinson, and ten other individuals who bore the common Outer Banks’ surnames of Ballance, Basnett, O’Neal, and Rollinson sold their interest in the station property to Frederick H. Peters for $10. (No deed or record indicates how the property came into the hands of the Rollinson family, but it may have reverted back to them as previous owners.)

Hailing from Richmond, Virginia, Peters was not a local, but he regularly visited Hatteras Island to hunt, reaching his vacation home via ferry.

According to documentation, Peters tore down the rebuilt and weather-battered tower soon after purchasing the property, but he gave many of the station’s usable buildings and structures to local residents.

The station remained a private residence in the decades that followed, and the property was recently sold to another private owner who wanted to bring the historical aspects of the original 1918 station to life.

“The gentleman who is doing all of this has a love for history, and he and the developer came up with the idea to create a replica of the Creeds Hill Tower and observation post,” said Chickey.

The Creeds Hill Lookout Tower project

Rebuilding a 45-foot-tall historic tower in one of the most weatherworn stretches of Hatteras Island is not an easy undertaking.

The solution to erecting a historically accurate tower that could stand up to the elements was to follow the original design as closely as possible, while using modern materials and techniques to ensure it could last.

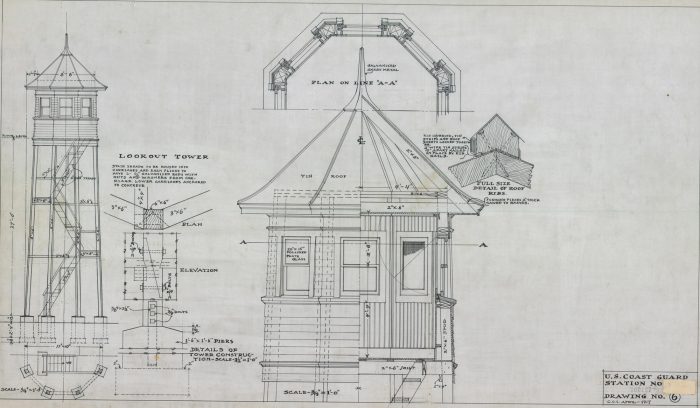

The blueprints for the tower stem from an intricate 1917 design that has all of the relevant specs included.

The base of the tower is roughly 24 feet in diameter, and it narrows as it extends into the sky to a lookout area that’s 10 feet wide. Staircases lead to the top observation area, which is somewhat enclosed but provides plenty of vantage points to scour the ocean waters for trouble.

“When you look at the original design, it is pretty darn close,” said Chickey. “The [replica] matches the design almost to a T – it’s just being built with steel instead of wood in its recreation.”

In addition to the pilings that were driven 50 feet into the ground with specialized equipment, the new tower has a concrete foundation, and the backbone of the structure is being constructed with galvanized steel.

“It is the harshest environment that there is, especially in that particular location, so some of the [material] manufacturers are also using this as a test case for how well the materials hold up over time,” said Chickey.

When the tower is complete, it won’t be open to the public, as the home remains a private residence, but it will certainly be a visible attraction to anyone cruising along N.C, Highway 12.

The estimated date of completion is hazy, and the progress of the work is highly dependent on the weather, just like all projects on the Outer Banks.

But the moving parts are in place and on site, and in the next few months or even weeks, islanders will have a restored landmark that hasn’t been seen for a few generations.

“We’re happy to be a part of this,” said Chickey. “We’re semi-locals ourselves, so this is such an exciting project to be a part of. And it’s definitely one of a kind.”

The post Replica of historic Creeds Hill Lookout Tower being constructed in Frisco appeared first on Island Free Press.

Add to favorites

Add to favoritesCredit: Original content published here.